Does The Hot Hitter Exist?

I finally get into the data to try to answer the question - does the hot hitter exist in Major League Baseball?

Big time research piece here! I have long been a skeptic of the “hot hitter”. I’ve met very few people who agree with me on that. Almost every time when I’ve argued with someone about it, we seem to be coming at each from different angles - but still, I know they don’t actually believe me.

So let’s define our terms first. What I am talking about when I am talking about a hot hitter is this:

A hot hitter is a hitter who is temporarily elevating their performance due to factors that are not just random luck.

So yes, I cannot argue that hitters do go through “hot streaks”. Of course, every player during a year will have streaks of consecutive games where they perform way better than their average. A .250 hitter doesn’t hit .250 every week - duh!

But in the context of fantasy baseball and betting and whatnot, what we’re talking about when we’re talking about a hot hitter is a hitter that should be expected to perform better than their average in the near future. This is what you mean when you call a hitter hot in the context of fantasy baseball. You see it every day on Twitter. Let’s bet on Luis Robert to homer tonight because he’s been really hot this week! Let’s fade Matt Olson because he’s hitting just .210 over his last 10 games.

The purpose of this analysis is to determine whether these temporary boosts in performance in the near term after a hitter gets “hot” really occur.

So let’s not waste any time, here’s what I’ve got for you.

Test #1 - The Simple Test

The challenge we have is deciding how to determine when a hitter is actually hot. I’ve done this two ways for the purpose of this post. A simple way, and a much more complex way.

The simple test was this:

Take qualified hitters from 2022 (450+ AB to avoid the guys that had serious injuries that could skew this)

Loop through each one of them

Every day of their season, find their last five games average fantasy points and their next five games average fantasy points

Isolated the times when the hitter has averaged 40% more fantasy points than their season average in their last five days

Deem the hitter “hot” on that day

See how their next five games went the times they were hot

To me, this is pretty sound. I think everyone would admit that you can score 40% more fantasy points in the last five games by sheer random luck. Maybe you just have a bunch of guys on base in that span and drive in more runs, or maybe all of your bloops are falling in. But, with the amount of data we have here - that shouldn’t be a concern. I found 2,506 occurrences when a hitter had been called “hot”. Let’s take one example to make our point.

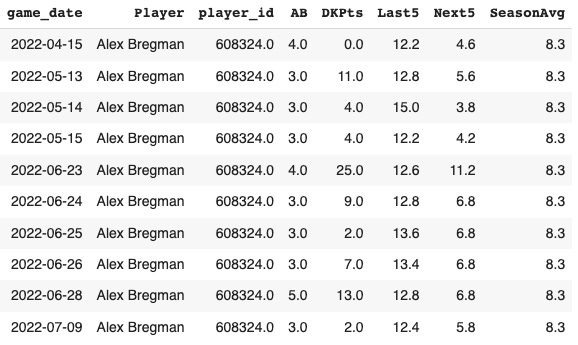

We will look at Alex Bregman, because his name starts with A and he played a lot last year.

Here are the times when he was hot:

So for example, take the first row. On April 15th, he had averaged 12.2 fantasy points in his last five games. His season average would turn out to be 8.3, so this 12.2 was 47% higher than his season average - and I deemed him hot.

From April 15th to April 20th, Bregman played five games and averaged 4.6 fantasy points, would you like more proof?

(0 + 2 + 14 + 7 + 0) / 5 = 4.6. You see that 4.6 above in the first row of the “Next5” column, showing that his next five games after I called him hot he averaged 4.6 points.

One data point here is, of course, completely meaningless. But what I did next was for each player, look at each time they got hot and then found the average of their next five while they were hot.

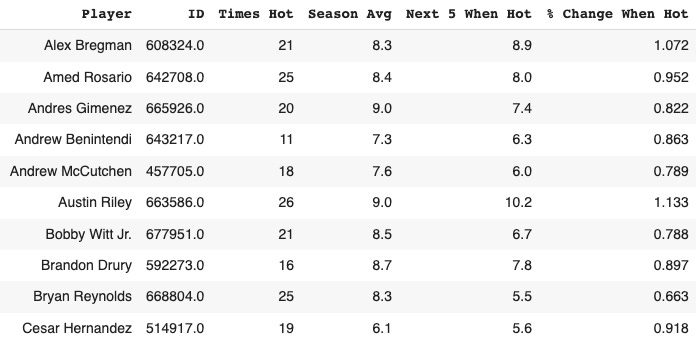

There were 129 players studied, and as mentioned above, those 129 players got hot 2,506 combined times. Here’s a sample of the resulting data:

So how to interpret that is to say:

“Alex Bregman got hot 21 times. He averaged 8.9 points in his next fives games after being called hot, and for the season he averaged 8.3 points, so he was 7% better in the short term after he became hot”.

It’s not completely perfect, but I think this is a sound way to break it down. Okay, now we can add a column to find the % change for each player to see what their change was when hot as compared to the season average.

So Bregman was 7% better, Rosario was 5% worse, etc. So then, to get our final answer, we take the average of that whole “% Change When Hot” column.

IF HOT EXISTS - we would expect this number to be significantly above 1.0. If a player can be hot, we would absolutely expect them to perform better in the short term after they’ve just had a big streak of games as compared to just the normal next five situations. If hot existed, it wouldn’t happen every time, but over a big sample like this - we would absolutely expect this number to be significantly above 1.0.

The number we find is *drumroll*……………………… 96.7! Meaning hitters were 3.3% worse in their next five games after being deemed “hot” as compared to the normal situation. 3.3% is a small percentage. Taking 3% off the average player would cost them just 0.3 fantasy points per game.

I checked different day counts to use (so say use your last and next 7 games instead of five), here is how that shook out:

3 days: 3,462 data points, -2.4% change

5 days: 2,506 data points, -3.3% change

7 days: 1,905 data points, -4.3% change

10 days: 1,237 data points, -6.8% change

You thinkers out there may have realized a bias I have here. Since I am comparing to the full season average, that makes it more likely that the hitter’s next few games after scoring a lot of points will be a negative change.

Think of it this way, if I used an 80-day average on players that played 162 games, it’s clear to see. Using that 80-day thing, there would only be a day or two in the season where it had 80 days before and 80 days after. So if the 80 days before were 5% below the season average, then the 80 days after would have to be 5% better - because I’m comparing to the season average, which took into account both before and after the cut-off point already.

So the bigger the day sample I’m using gets, the more you’re going to see that % change number gets pushed below 1. But with using just small samples like 3, 5, and 7 days - that bias is almost fully negated because we’re talking about a very small % of the season’s total games.

One more thing to drive the point home even further. I looked at the times when a hitter had averaged double their season average over the last three games and then saw what they did in the following 3 games. That happened 782 times, in the three days following the huge three games, they scored 5% below their season average. The same bias occurs here, but -5% certainly shows a serious lack of evidence for any kind of “hot hitter”.

None of this is perfect, and I’m sure a person smarter than me could poke some holes in my methodology here - but I would still say confidently that this is serious evidence that the hot hitter doesn’t exist as most people believe.

Test #2 - More Complex

This one has been months in the making. Last year, I developed a “hot hitter” tracker that would run every day and publish the names to the Daily Notes. It’s still running, and this year I have been logging those hot hitters every day.

A hot hitter by this method is defined much more intelligently, I would say. What that script does is find hitters that, over their last seven games as compared to their career averages (2021 through that current day), have

Whiffed significantly less

Chased significantly less (swung at pitches out of the zone)

Hit the ball significantly harder on average

I use 3% for the first two bullet points and 3mph for the third. So, for example, here were the hot hitters on June 19th of this year:

So take the first row there, in the last seven days, Betts had an 89.6% Contact%, a 10.6% Chase%, and a 96mph average exit velo. Those all beat his career averages by three points or more, so I called him hot.

I picked this method because I was thinking about how people always say a hot hitter is “seeing the ball really well right now”. Well, if that were true - then they would certainly be whiffing less, chasing less, and probably hitting it on the screws more often (higher EV) than their career averages up to that point. So I thought this was a pretty intelligent way to do it.

So the next thing to do was to find each hot hitter and then see what they did in the ten days (days, not games) following their hot designation.

So far this year, there have been 581 instances of a hot hitter where I had 10 days of future data to compare. I looked at four categories

xwOBA

OPS

K%

BB%

So for each of the 581 hot hitters, I have the data on their career averages (including no data from after they got hot - so we don’t have the bias I talked about above in this one) for those categories and what they did the 10 days after I deemed them hot.

So let’s do another individual example to make it clear. I already talked about Mookie Betts on 5/19, so here’s that row in the resulting dataset:

So, in the 10 days (this will usually be 7-9 games played) following his hot designation, he had 39 PA and put up a .348 xwOBA. His “career” (again this is only going back to 2021, it’s not actually the career) xwOBA prior to that was .356. That’s a very slight 2.2% reduction in xwOBA after he got hot. Not significant at all, I would call that “neutral” - no change.

So I have a ton of data here. I binned each % Change number into one of three categories:

Positive - their next 10 performance was 5% or more above their career average

Negative - their next 10 performance was 5% or more below their career average

Neutral - their next 10 performance was within 5% in each direction of their career average

And here are the results for each category!

xwOBA

Average Change: +0.9%

Positive Change Rate: 41%

Negative Change Rate: 37%

Neutral Change Rate: 22%

So hitters did beat their career average more often than they got worse, but the difference is very slight, and the average change didn’t even reach 1%. A 1% increase on a .350 xwOBA would take you to just .3535 - not much of a change.

OPS

Average Change: -1.9%

Positive Change Rate: 40%

Negative Change Rate: 49%

Neutral Change Rate: 11%

More hitters got worse than got better, but again - the average change was not significant. A 2% reduction would take an .800 OPS to .784 - not a huge difference between those two numbers.

K%

Average Change: -2.0%

Positive Change Rate: 42%

Negative Change Rate: 44%

Neutral Change Rate: 14%

Very similar to OPS here. Hot hitters went on to strike out 2% less in their next 10 days after being deemed hot. That would take a 22% K% to a 21.5% mark - again, not a significant difference.

BB%

Average Change: -2.4%

Positive Change Rate: 42%

Negative Change Rate: 52%

Neutral Change Rate: 6%

This is the biggest change. Hot hitters walked 2.4% less in the short term. That takes an 8.0% BB% to 7.8%. Not much of a difference, but the biggest one we have here

I checked to see if hot hitters were swinging more after getting hot. This made some sense to me because maybe the recent success had them feeling more confident and being more likely to let it rip - but alas, I found no difference at all in swing rates (average change of just -0.4%).

So even when doing this in a more intelligent way that makes sense to the real-life human mind, we find no elevated performance in the short-term after we find that a hitter is “hot”.

This means one of two things

Hot doesn’t exist

I just don’t know how to locate a hot hitter

I think it’s the first bullet point, but I’m not willing to declare total victory here.

The main lesson to be learned here is that performance in the short-term past does nothing to predict performance in the short-term future. If anyone is saying “bet on this guy today because he’s been hot lately!” - don’t do it, and probably stop taking that person’s advice altogether.

People will then go on to say that things like “swing changes” or “approach changes” can make a difference. And sure, that can happen. There are definitely instances where a player just figures something out and then from there on goes and elevates his performance. But that’s the exception rather than the rule. Most short-term improvements are just because of random factors that should not be counted on to stick around. You will do much better at predicting the future if you ignore these “hot” and “cold” streaks.

Again, I’m not declaring total victory here. This is a complex thing, and maybe someday we’ll find a way to deem a hitter “hot” that actually works! I doubt it, but maybe!

I really didn’t know what was going to come from this study, and I can say I’m pretty happy that it confirms my prior belief! But maybe there’s some subconscious bias here that drove me to find these results. I think my process was smart and fair and sound, but anything is possible. Feel free to drop me your ideas and criticisms!

I would love the see the cold hitter results and how they performed after cold streak.